The Congress of Racial Equality (Core) was established in Chicago in 1942 on the University of Chicago campus. It was founded on the theme of change, on the basis of instilling change through nonviolent techniques. In 1955 CORE went to the South to provide nonviolence training to demonstrators there during the time of the Montgomery bus boycott. The work of the Congress of Racial Equality was dangerously influential.

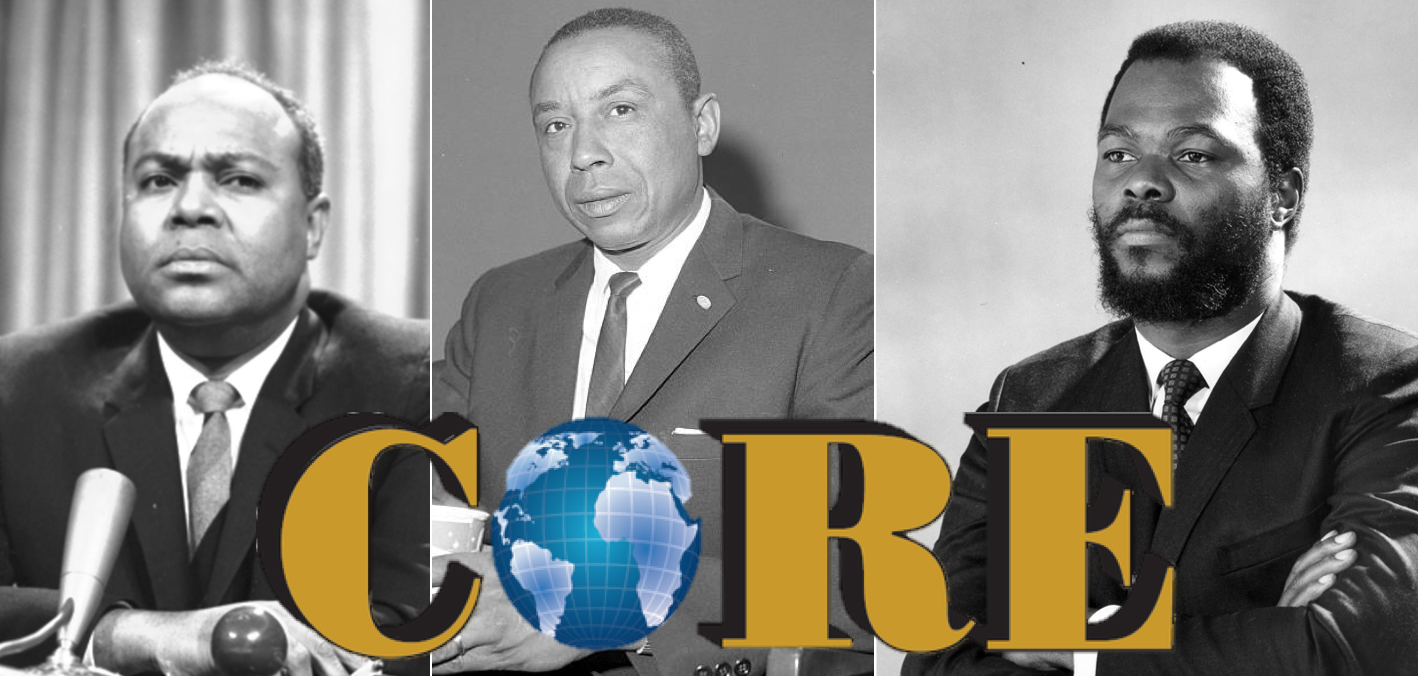

June 1964, three of the organization’s activists were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan while working in CORE’s Freedom Summer Voter Registration project near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Among the lost lives were Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney, a civil rights activists who participated in the Freedom Rides in 1962, another civil rights effort organized by CORE in which busses traveled through the south challenging the practice of segregation. James Farmer cofounded CORE in 1942. Farmer, a graduate of Harvard university in 1941, was an advocate of nonviolence as a method for desegregation. Farmer was a longtime promoter of integration, but as incidents of racial violence increased blacks began to believe that political power, not integration, would be a more secure goal for attaining equality. Farmer actually lost the run for a seat in the House of Representatives against Shirley Chisholm in 1968 after resigning from his leadership position from CORE in 1965.

Supporting Nixon in Pursuit of Soul City

As director, Farmer was replaced by Floyd McKissick. McKissick was the first Black student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Law School whose college experience contributed to his displeasure of integration, he’d been committed to black separatism. He dedicated much of his energy to rebuilding Soul City, a North Carolina town run by Blacks with a mission of Black empowerment whose funding was surprisingly provided from Republican President Richard Nixon. Soul City had been an attempt to provide some form of retribution to blacks with the governments failed promise to provide 40 acres and a mule. As a lawyer he defended many freedom riders who’d been arrested as a result of their demonstrations against racial segregation, defending those who sat in white sections at lunch counters and movie theaters.

Following McKissick as director, Roy Innis was a politician whose views highly contrasted with the majority of the African American community who saw him as being too right-wing and radical. He did not share his predecessors nonviolent stance on civil disobedience and viewed integration as a negative force that robbed blacks of their own cultural heritage and identity. Under the banner of black power and what he termed “pragmatic nationalism”, Innis slowly removed white members and leaders from CORE by targeting his focus on black segregated schools, black business and community surveillance of the police. Although most African-Americans saw black power’s methods as too radical they continued to benefit from the results of their targeted approach to empowered black communities.

Changing Tide, Contrasting Views

The contrast between these leaders in CORE illustrate the versatility of perspectives in the Black community, ranging from integration seeking freedom riders to militant black power black nationalists and everything in between. All of these leaders saught better conditions for black people in the United States, a complicated task in a post-slavery white supremacist society. The complexity of this task can be seen in the varied opinions on how to go about doing so. The difference in opinion is majorly influenced by ones own life experience. For example, CORE’s first director, Farmer, was an avid supporter of integration while McKissick, who was the pioneer in his experience of integration at University of North Carolina, advocated highly for Black separatism. There is no right way to pursue political power or equality as an oppressed minority class, methods change as the times change and opinions are heavily influenced by individual perspectives. Regardless of one’s individual approach, so long as one is committed then diligent change can and will be made in the favor of the group they’re fighting for and there are so many changes to be made and so ways to do so.