For the past few weeks I’ve been watching How to Get Away with Murder, another one of my favorite legal dramas is Scandal, for the simple fact that I love seeing Black women in power. The fact that I studied law in college makes the plots all the more interesting, aside from the fact that in both shows the director, Peter Nowalk, frames the women as unlovable and desperate for male attention. It seems as though, even when we’re beautiful, intelligent and successful the historic relationship between men and women in our society reduce women to sex. How can we protect the image of a woman whose been historically degraded and devalued? How can we expect Black women to feel safe in a society where their image has been constantly depreciated in the media and even in the law. The unequal protection enforced between Black and White women is staggering, according to a study done by the Dallas Times Herald, “the average prison term for a man convicted of raping Black woman is two years, whereas the average term for a Hispanic woman was five years and for a white woman ten.” The law does very little to protect Black women, even when we dedicate our lives to protecting the law. We can see this most explicitly in the case of Alberta Jones.

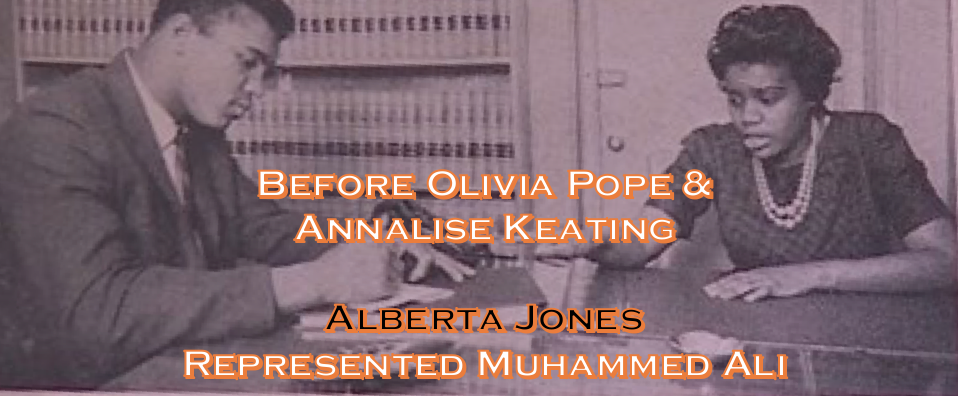

Alberta Jones was the first black female prosecutor of Louisville, Kentucky. She was one of the first Black women to pass the Kentucky bar after Sally J. Seals White who was the first Black woman to be admitted to the Kentucky bar. Jones was the first female city attorney in Jefferson County and was appointed to be a prosecutor February 1965. She had always been a scholar. After graduating from Louisville high school she attended the Louisville Municipal College for Negroes. During desegregation when her college was merged with the University of Louisville she graduated third in her class. Although she was accepted into the University of Louisville Law School, she transferred after the first year to Howard University School of Law, there she graduated fourth in her class. After completing Law school she opened her own law office where she was able to represent champion boxer Muhammad Ali. Like Ali, Jones was also a civil rights activist, participating in the March on Washington as well as several marches in Louisville. She established the Independent Voters Association and rented several voting machines to teach classes for African Americans so they could learn to use the technology to vote for the candidate of their choice. Jones was also an active member of the Louisville Urban League and the NAACP.

Alberta Jones was an accomplished woman, she graduated at the top of her class during the Jim Crow era and in desegregated schools. She served her community and dedicated her life to protecting the law, but the law fell short of protecting her. Jones was murdered August 1965, six months after being appointed the prosecutor position. Her body was found in the Ohio River. Initially her death was attributed to drowning, but an autopsy revealed that she’s been hit on the head several times before being tossed into the water. Jones’ sister, Flora Shankiln recalls her sister’s death, “She was abducted by 3 to 4 people,” she told interviewers from WDRB, “She drowned because they beat her until she was unconscious.” Now over fifty-one years later no one has been charged with Jones’ murder. She was a Black women breaking down barriers, doing things that no other woman had done before. Jones was the first African-American woman to pass the Kentucky bar exam. As an attorney, Jones represented legendary boxer, Muhammad Ali and became the first woman ever to serve as a prosecutor in the Commonwealth. Her inexhaustible success was inspiring, however in made some people, who depended on the oppressive state of Blacks, uncomfortable. Seeing a Black woman rise to power in the criminal justice system within a white supremacist society, where laws are based on protecting white supremacy, is tremendously threatening.

After her body was found and the autopsy revealed foul play, the case was still dismissed. Life was brought back into the case in 2008 when the FBI matched a fingerprint found in Jones’ car with a man who was 17 at the time of the murder. Jones was unmarried, living only with her mother and sister. However, the lead was not pursued and the case wasn’t reopened for a lack of “sufficient evidence”. Dr. Lee Remington Williams, an attorney and professor at Bellarmine University, is intending to write a book about the life of Jones, but feels that the story is incomplete with Jones’ case left unresolved. In order to persuade police to move forward with investigation this past fall Williams’ submitted a seven-page letter to the Louisville Metro Police Department, including several years of her research on the case. “Alberta Jones was a phenomenal person who spent her entire life advocating for others,” Williams explained to WDRB, “She fought for everyone else, and it’s time that people stood up and fought for her.”

Williams is right, the case of Alberta Jones is heartbreaking. Jones was the first woman to ever serve as a prosecutor for Commonwealth and her death should be taken seriously and investigated with more significance, but According to the Commonwealth’s Attorney, the case was reviewed at the time, and there is not enough “sufficient evidence” to reopen it. How is a matching fingerprint found in the victim’s vehicle insufficient for re-opening investigation? This can only be so if our criminal justice system values protecting the life of a young male murder over that of the life and legacy of a Black woman. It’s devastating, but we can clearly see this trend proven to be true throughout American history.

Alberta Jones’ is well deserving of re-opening the investigation on her case, her justice it is long over due. #SayHerName #NeverForget